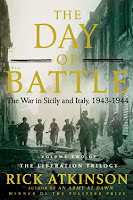

TITLE: Day of Battle: The War in Sicily and Italy, 1943-1944

TITLE: Day of Battle: The War in Sicily and Italy, 1943-1944AUTHOR: Rick Atkinson

PUBLISHER: Simon & Schuster

RATING

5/5 "Battle of Hoth"; 4/5 "Battle of Wits"; 3/5 "Battle of the Sexes"; 2/5 "Battle of the Bands"; 1/5 "Battle for Terra"

SCORE: 4/5

World War 2 is our low-fat war. One we can indulge in as much as we want, secure in the knowledge that the glorious fallen do not remain to lard our consciences, but rather have been transported to light, airy heaven. With other wars, we may have to rationalize, but there's little doubt that fighting the Nazis was the Right thing to do.

When you get to the question of when and where we fought them, though, things get a little stickier. Not every battle or campaign is so easy to justify, and as Rick Atkinson shows in "Day of Battle", the Allied invasion of Sicily and Italy is the ten-pound ball of deep-fried butter ruining our no-guilt diet. The campaign left 100,000 soldiers dead, perhaps four times that many wounded, without striking any decisive blow against the Germans or sufficiently distracting them from other theaters. Was it worth it?

Mr Atkinson equivocates on the question, but he does so beautifully. "Day of Battle" forms the second of Mr Atkinson's planned "Liberation" trilogy following the history of US armies in the major European campaigns of World War 2. The series began with 2002's Pulitzer Prize-winning "An Army at Dawn", an engaging, in-depth history chronicling the US landings in North Africa. "Day of Battle" maintains this high standard of writing, even if it lacks the former book's driving narrative.

Mr Atkinson brings a humanist touch and eye for detail to the little-studied invasion of Italy. His book combines memoirs, first-hand as well as official accounts, and stacks of letters to from soldiers to those waiting at home. This intimate look at the war, combined with a heavy dose of poetic license, makes this a surprisingly readable book despite its 600-page-plus length. The only fault in the style is the aforementioned poetic license, which crops up in Mr Atkinson's tendency to embellish his descriptions. "The dappled sea stretched to the shore in patches of turquoise and indigo," he says, which is nice to read but hardly good history.

The supporting maps are likewise something of a mixed bunch. While clean and informative for the most part, in the paperback edition I read a number of printing errors had left some names with missing letters, so that "Monte Lungo" is rendered "Lun o" and Major-General Hawkesworth "Awke w r".

The level of detail of Mr Atkinson's account is, however, amazing, covering the US involvement in the campaign from the Anglo-American conference in May 1943 where it was conceived, to its climax in the fall of Rome in June 1944. Altghough the descriptions of acutal battle are sometimes a little vague, "thrusts met stout resistance", "a flanking attack ... unhinged the German line", Mr Atkinson's coverage of the leading personalities, from US commanders George Patton and Mark Clark, to divisional commanders like Lucian Truscott and even more junior officers, is much stronger. Mr Atkinson projects genuine respect and admiration for these men, though you feel he might be too easy on them sometimes. Mr Atkinson lists their ailments and worries sympathetically, but I can't stomach commanders sleeping in sprawling Italian villas and complaining about stress or tiredness, when a dozen kilometers away their men are getting dismembered by the truckload. Clark in particular gets off lightly, despite coming across as slighly insubordinate and egocentric.

Rather, Mr Atkinson saves his venom for the real enemy: the British. "Day of Battle" is a fine account of the campaign, provided you are utterly uninterested in the involvement of the British, Canadians, Polish, New Zealanders, Indians and other nationalities who made up the Allied force. Whenever the "cousins" do pop up, they soon disappear under a barrage of criticism for poor leadership, lack of offensive spirit, and failure to support or appreciate their American allies enough.

The most troubling part of the book, however, is Mr Atkinson's attempt to justify the campaign as a whole. In "An Army at Dawn", he convincingly argued that the African campaign helped steel US forces for the war in Europe. The argument doesn't work as well here, especially as he himself notes that soldiers not killed or wounded tended to become psychiatric casualties after 200-240 days; men can only be tempered so far before they break. Instead, Mr Atkinson falls back on the stale comfort that, in the words of war correspondent George Biddle, certain qualities "give war its justification, meaning, romance and beauty. The qualities of valor, sacrifice, discipline, a sense of duty". This flies in the face of the evidence Mr Atkinson presents in the previous 600 pages, that the war was horrible, meaningless, savage and hellish.

Far better is another quote by Biddle, "I wish the people at home, instead of thinking of their boys in terms of football stars, would think of them in terms of miners trapped underground or suffocating to death in a tenth-story fire." Sometimes, I think, it's only right that our consciences should be troubled.

No comments:

Post a Comment